Soon to retire General Manager for the United Potato Growers of Canada (UPGC) Kevin MacIsaac looks back on how the potato industry has changed over his career.

I’ve never been one to spend much time looking backwards, but sometimes one must do so, to see how far ahead we have come.

Having the vantage point of 40 plus years to look out over the potato industry, one could expect many changes. Some were not even predictable. Many are positive accomplishments. Some are not and point to challenges ahead of the industry.

Here are some top items which come to mind:

Technology

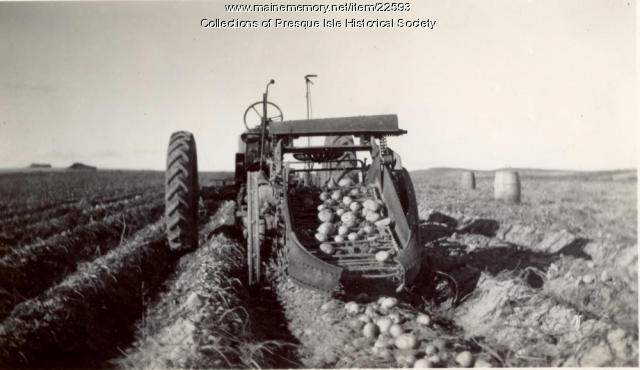

The most recognizable trait has been the great improvement in technology to grow the crop. As a kid in elementary school, one remembers the potato crop was dug with a beater digger, filled into baskets, dumped into bags, and hauled to the cellars of the farmhouses. Labour was back breaking, and a step-up, came to a one-row Omni digger/bagger.

The shift to “bulk potatoes” transformed the industry with one-row semi mounted harvesters and 12-foot bulk boxes. Harvesters moved to mostly two-row diggers, with some four-row and six to eight-row configurations.

Windrowers came next — allowing growers to “dump” drills into the harvester row. Windrowers started at two-rows and moved to four-rows fairly quickly. The limiting factor in moving to six-rows was row straightness, as the windrower would have to straddle planter widths.

GPS technology bringing perfectly straight and spaced rows allowed that to happen. Even some 8-row windrowers are now in use. The net result is a harvesting unit that has moved from picking up two rows at a time to a 14- or 16-row capacity.

The economies of scale in harvesting are one of the main drivers in moving grower size from 100 acres to 500 acres to 1,000 plus acre production units. In recent years we see self-propelled harvesters with European style technology gaining popularity.

Planting of the crop has seen similar advancements. Some elite seed growers planted their crop by hand, but most commercial growers used a two-row pick planter which eventually became four-row for most. Six-row planters are common today and the next generation of very wide planters is becoming available as manufacturers have figured out a way to fold them and allow them to travel down narrow country roads.

Sprayers have moved from the FMC or John Bean high pressure, high water volume machines, to low drift, course, electrically charged droplets. Automatic rate controllers are standard and GPS commonplace. Many producers for years used 500 gal units with 60-foot booms and gradually moved upward to 1,000-gallon tanks and 90-120 ft. booms. Recent years have seen shifts to self-propelled units for their speed, hydrostatic transmission efficiency, and ease of entering rows off the headlands.

Aerial spraying while still popular in the west, has been banned from eastern provinces and no longer an option for those producers.

Storage and Ventilation

The advancements in potato storages have totally transformed an industry that used to see a market very dependent on the start of new crop, to replace those old crop potatoes that had been stored in conventual buildings and had reached the end of their life cycle.

Excellent insulation, through the pile ventilation, humidification, and refrigeration capability now allow potatoes stored in those buildings to reach their first birthday. Growers now check their fully computerized systems with an app on their phone.

With the extension of the storage season, the market for newly harvested fresh potatoes has been greatly diminished with quality out of storage matching, or even exceeding, out of field lots. Having received lots of oxygen, processing potatoes produce excellent colour and fry into that nice light colour that french fry or chip palates seem to love.

Successful long-term storage is of course dependent on sprout inhibition, and continued availability of those products is something industry needs to keep their eyes on.

Water Availability

For decades, farmers could anticipate a year or so in their history where there was not enough water to produce a good crop or maybe too much water during digging to slow down bringing in the harvest. In recent years, weather events have become extreme and commonplace, increasing the level of risk on the backs of the growers (something they are not compensated for enough).

In addition to catastrophic losses this has also created a production shift to areas of North America that have the best long-term access to water and the ability to apply it to their crops. As a country, our northern lakes in Western Canada continue to supply the water needed to grow the potato crops produced not only here, but in the western United States as it flows south.

Irrigation systems have become commonplace in what was once dry land production in many areas. The back breaking labour of moving pipe on hot days, continually being replaced by highly sophisticated, computerized, center pivots controlled by an app on the grower’s cell phone. Use of tile drainage to remove excess water and allow easier harvest from fields containing high value potato crops, has also gained popularity.

Crop Protectants

The fruit and vegetable sector of agriculture has, and continues to be, closely scrutinized by regulatory officials for the products needed to grow a healthy crop. The result of such a high standard of regulation, is that Canada produces some of the safest food in the world.

While envious of the available protectant toolbox in other countries, growers realize the safety of their agronomic practices while raising their own families on these farms. Consumer loyalty has been strengthened in the past year of COVID restrictions as shoppers became increasingly concerned with perceived shortages of grown in Canada produce.

Organic sales continue to grow at a slow pace, and what is truly amazing is the number of farms that now grow both conventual and organic potatoes in the same entity.

Market Trends

Probably the biggest trend in forty years is the shift in per capita consumption from fresh potatoes to processed products like french fries and potato chips.

After french fry manufacturers figured out how to blanche and quick freeze potato slices, what was once a small component has grown to represent 65 per cent of the industry. It continues to be driven by convenience, availability, great flavour, and innovative products.

The MacDonald’s all-day breakfast alone is responsible for such an increased demand for raw potato delivery. Coupled with availability in eating establishments that previously didn’t offer fries as meal selections, the growth is exponential. The greatly improved quality of raw, due to better management and storage of the potato crop has also made it a very profitable sector for manufacturers as they realize resulting higher recovery rates.

Chip sales continue to amaze the pundits with Nielsen data at the cash registers showing sometimes consumers just like comfort foods and will buy them for that pleasure.

The table sector has also seen major shifts in trends. For years, everyone wanted the big potatoes and threw out the small potatoes as culls. Now the little potatoes are a premium product and when coupled with tasty flavouring condiments and attractive packaging, they are helping to move the needle on fresh potato consumption again. Smaller family size, one parent families, and busy work schedules have all contributed to the rise of smaller size potatoes, smaller package size (from 50 to 10 to 5 to 2.5lbs), and less preparation time in the kitchen.