A cross country check-in on what to expect for potato diseases this growing season.

Late blight has and very likely always will be something Canadian potato producers need to be vigilant against. Changing weather patterns, effective late blight early warning systems and control products have reduced the risk in recent years. But as any grower knows, there’s no shortage of other potato diseases which can spell trouble during the growing season. Here are some to watch out for this year.

Late Blight

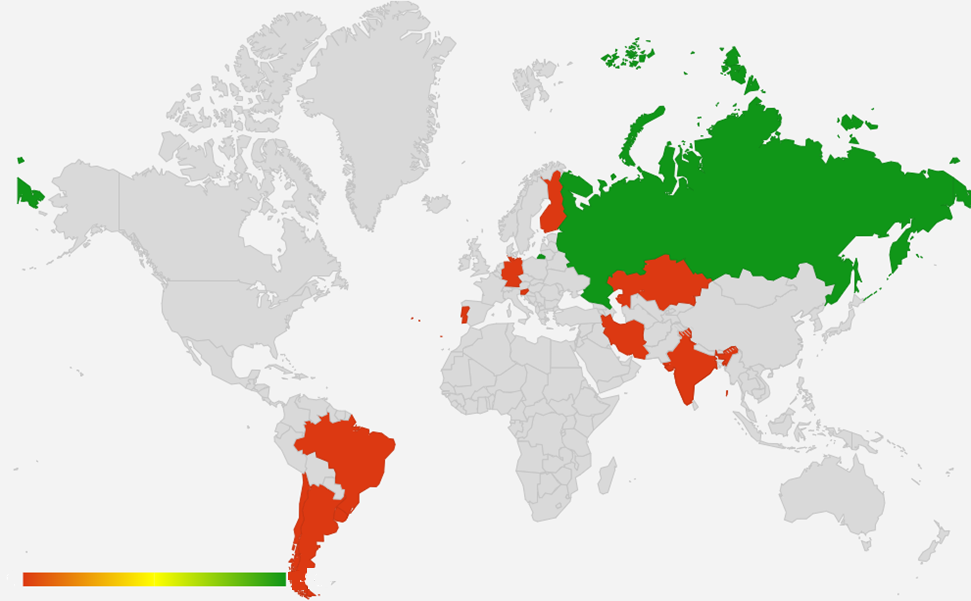

Phytophthora infestans, the late blight pathogen responsible for the ruinous Irish potato famine of the 1840s, has been the scourge of potato growers around the world ever since. In addition to the staggering crop losses it’s caused, late blight has also been the most expensive potato disease to manage, with a global cost of at least $6 billion according to some estimates.

It’s hardly a surprise, then, that late blight persists as the number one disease concern for most commercial potato producers in Canada. In the last few years, however, effective late blight warning systems and changing climate conditions have contributed to a dramatic drop in the disease incidence.

“There’s been one or two positive late blight findings in the last two or three years, but we haven’t had widespread outbreaks,” explains Dennis Van Dyk, vegetable crop specialist with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs.

“We have a very good monitoring program here with a spore trapping network that’s acted as an early warning sign for our growers and allowed them to be proactive in spraying.

“Late blight is always front of mind, but at this point, whether it’s because of the weather or because of the spore trapping network, I think we have a fairly good handle on it.”

Vikram Bisht, a plant pathologist with Manitoba Agriculture and Resource Development, notes commercial potato fields in Manitoba have been late blight-free since 2018, thanks in large part to the success of the late blight spore trapping network which alerts Manitoba growers when P. infestans spores have been detected in the province.

“There were no reports in 2020 of late blight, even though we did trap some late blight spores,” says Bisht. “We were able to warn growers and they upped the ante on spray scheduling, which was extremely helpful.”

Dymtro Yevtushenko, research chair in potato science at the University of Lethbridge, reports there were a few instances of P. infestans spores being detected by the Potato Pest Monitoring Network in Alberta last year, but not enough to raise alarm bells.

“It wasn’t above a certain threshold that makes us concerned,” he says. “For the last two years now, there has been no late blight incidence, which is great.”

Because of the mild and moist Maritime climate in Atlantic Canada, Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick have historically had more issues with late blight than most other potato-growing regions in the country. But conditions have changed in recent years, with warmer, dryer summer weather that’s reduced the threat posed by P. infestans pathogens.

“Because of the weather pattern that we’ve been in for the last four or five years, late blight has dropped way down on the list diseases of concern,” explains Lorraine MacKinnon, potato industry co-ordinator with P.E.I.’s Department of Agriculture and Land.

“We have gone a few seasons now with no detection of late blight spores on the Island. There hasn’t been inoculum sitting around,” she adds. “There are also changing strains of late blight that are perhaps a little less aggressive in the foliage, and we do have a lot of effective control products.”

MacKinnon, along with the other experts, cautions growers against letting down their guard against late blight, which is capable of wiping out an entire potato field in a matter of days and also affects the quality and storability of tubers.

“There’s always a risk that late blight will return to P.E.I. fields. Weather-based predictive modelling and spore traps are very effective in in-season, but they can’t predict the situation in advance of a growing season,” she says.

Khalil Al-Mughrabi, a pathologist at the Potato Development Centre with the New Brunswick Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Aquaculture, agrees with the sentiment as late blight has not been found in the Maritimes the past three years. He notes though that through a national research program, work continues on developing new disease management strategies as well as assessing the efficacy of registered fungicide products against the predominant strains of the late blight pathogen.

Al-Mughrabi says in New Brunswick, a late blight forecasting program based on weather conditions conducive for late blight development, and a spore trapping system which covers the potato growing regions in the province, are being actively implemented in order to predict for late blight.

Van Dyk notes Ontario is keeping an eye out for a new late blight strain, US-25, as well as a late blight look-a-like, Phytophthora nicotianae, which is a related species to P. infestans and causes foliar symptoms similar to late blight. Both have been detected next door in New York state, so growers are urged to send samples of any plants exhibiting late blight symptoms in for strain identification testing.

PED

While the late blight situation has improved, there is rising concern across the country about another crippling potato disease — potato early dying (PED) complex.

“One disease that stands out in the past few years is PED,” explains MacKinnon. “Because we’ve been having warm, dry summers, we’re seeing a lot of challenges with potato early dying, and this is impacting yields for the processing varieties… Producers here are quite concerned about it.”

Fumigation, which kills the verticillium and root lesion nematodes associated with PED, is a common control measure for the disease, but it’s not permitted in P.E.I. MacKinnon says as a result, Island potato producers may be looking at adding a biofumigant crop to their rotations this year.

“Mustard is becoming quite common for a couple of reasons. Studies show mustard to be effective against verticillium in the soil, but it has some benefits for wireworm control as well,” says MacKinnon.

“There’s also a lot of research being done on the effect of sorghum-sudangrass, pearl millet and other rotational crops that can reduce the amount of verticillium and/or root lesion nematode in the soil.”

Van Dyk says while PED may not be as big a problem in Ontario as it is the Maritimes, it’s definitely on the radar of growers in his province with growers who had problems with it, fumigating and looking into other soil health measures.

“We had a fairly good harvest, so if growers were going to apply a fumigant for fields that they thought were high in verticillium and nematodes, they had an opportunity to do that in the fall because there was time to do it,” he explains.

Bisht notes black dot and verticillium wilt, both within the PED complex of diseases which cause early dying, have been increasing in importance in Manitoba in recent years. While the weather plays a large role in the incidence of both diseases, Bisht expects disease pressure will remain high this coming season in areas with a history of black dot and verticillium wilt.

Yevtushenko says concern over PED is increasing in Alberta as well as a changing climate is raising the risk of it.

“The planting area is expanding, and crop rotations may get shorter, and this will eventually lead to higher accumulation of verticillium in the soil, so with higher pathogen pressure we anticipate that the incidence of this disease will probably go up,” he explains.

Provincial Break Down

- Blackleg in Manitoba — According to Bisht, cool, wet planting conditions last spring led to a relatively high incidence of the bacterial disease in Manitoba potato fields last year which not only affected yields, but also caused blackleg trouble in some storages. Bisht says extra care should be taken with seed cutting as a result to reduce the risk of planting blackleg infected seed.

- Soft Rot in Ontario — Van Dyk says imported seed issues caused by bacterial pathogens such as Dickeya dianthicola and Pectobacterium parmentieri have become a pressing concern for Ontario potato producers. He urges growers to plant certified high-quality seed, test seed lots if they can to ensure they are disease-free, grade out for suspect seed, and be watchful for the first signs of bacterial soft rot in potato fields like spotty emergence and plants with less vigour.

- Early Blight in Atlantic Canada — Al-Mughrabi notes this disease was a challenge in potato fields in the Maritimes region last year due to lack of rain which stressed plants and favoured early blight development. “If the weather next season continues to be dry, a similar trend can be expected for early blight,” he explains.

- Common Scab in P.E.I. — MacKinnon points out the province’s drier weather in recent years has meant less moisture is available to tubers as they’re starting to initiate. “Because of that, you can get more common scab showing up, and it’s a very tricky disease to control,” she says.