The conversation had barely settled when the JKUAT team a group of researchers and technicians from the JKUAT Biotechnology Department, all coincidentally hailing from Eastern Kenya (Dr. Cecilia Mweu, Dr. Agness Kavoo and Mrs. June) and specializing in potato tissue culture walked into the ADC Molo Potato Unit. Their visit, intended to strengthen collaboration on clean seed production, quickly sparked a lively discussion about the future of potato farming in Kenya.

As the team toured the tissue-culture labs and later joined a meeting at the ADC molo office, one question kept resurfacing, lighting up the discussion:

Why not take potatoes to the lowlands of Eastern Kenya?

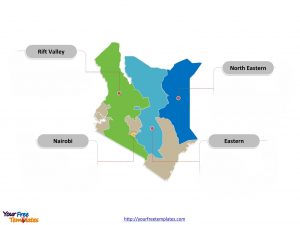

For years, Eastern Kenya farmers have battled unreliable rainfall, shrinking maize yields and the mounting pressures of climate change. Maize has long defined farming in the region, but shifting weather patterns are prompting a rethink of which crops truly make sense for the future.

Traditionally, potatoes thrive in midland to highland areas like Nyandarua, Narok, Meru and Nakuru. But with advances in irrigation and new heat-tolerant potato varieties, this once high-altitude crop is steadily finding its place in the lowlands and riverine zones of Eastern Kenya including areas along the Kaiti, Thwake, Kikuu, Mwilu, Tana, Thiba and Athi rivers.

New varieties for a changing climate

According to Mrs. Getrude, a Manager at the Agricultural Development Corporation (ADC), potato farming in the lowlands is not only viable it is increasingly attractive.

“Potatoes can be planted in the lowlands, but not all varieties will thrive there,” Getrude pointed out during the meeting.

“Wanjiku, Unica and Nyota are wonderful varieties that perform very well under irrigation or limited rainfall. Within a short period you can harvest potatoes often yielding up to five times more than maize from the same acre.”

These improved varieties mature early typically within 90–100 days and require far less water than maize. Their high yields and resilience make them ideal for areas with shorter or unpredictable rainfall seasons.

Mr. Mike, ADC biotechnologist expert present, emphasized that Nyota was specifically bred for lowland environments. It is high-yielding, drought-tolerant and has excellent dry-matter content, making it suitable for both table

consumption and processing.

High yield, high nutrition

While farmers in many Eastern Kenya counties harvest only 8–10 bags of maize per acre, potatoes under irrigation can produce 40–50 bags per acre, maturing faster and offering significantly better returns.

Potatoes also provide superior nutrition. They are rich in vitamins and minerals including vitamin C, potassium and iron making them a valuable crop for improving household diets, especially in regions prone to food insecurity.

A step toward food and income security

County governments and agricultural institutions are now encouraging farmers in Kitui, Makueni and Embu to diversify into potato production under irrigation. The goal is clear:

to reduce dependence on maize, increase household incomes and strengthen food and nutrition security as the climate continues to evolve.

As Getrude emphasized:

“With the right varieties, good management and reliable irrigation, potatoes can transform farming in the lowlands faster, better and more profitably.”

So why not the lowlands?

If potatoes can grow well, yield more, mature faster and nourish better, the question remains:

Why not take potatoes to the lowlands of Eastern Kenya?

With the JKUAT team advancing tissue-culture technologies, ADC providing certified seeds and CIP providing adaptable varieties and counties expanding irrigation, the region could be on the brink of a quiet potato revolution.