Students in tank tops with sunscreen-dotted noses walked down the rows of a potato field, frequently bending over to pluck leaves for sample boxes headed to the MSU potato lab.

Between sample boxes, students chugged from gallon-sized water bottles to get through the sweltering mid-July heat. Some took off their hats, drenched them in water, and slapped them back on before returning to the field.

This is all in a day’s work for the field pickers with the Montana State University Seed Potato Certification program. The program certifies potatoes grown for seed, which are sold to Montana producers and those in other states like Oregon, Washington and Idaho.

The program is designed to encourage the production of high-quality, disease-resistant potatoes through rigorous testing and inspection. MSU has one of the most extensive potato diagnostic labs in the country, said Nina Zidack, the program director.

By closely monitoring early generations of seed potatoes in Montana, the program is able to slow the spread of potato diseases and provide information for producers to better manage their farms. When Montanans buy seed potato starters from MSU, they are offered inspection and disease monitoring services through the program.

Nina Zidack, Director of the Montana State University Seed Potato Certification program:

“The most important function of the lab is to give farmers the information they need to grow disease-free potatoes.”

One part of the program is the summer leaf testing of all early generation seed potatoes. Around 30 students are working for the program this summer, split between the lab and the field.

On Tuesday, around 15 student pickers spread out a 20-acre field off Baxter Lane near Bozeman, one of the Kimms’ seed potato farms. It was their second day collecting leaf samples from this field. The pickers often work from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. every day.

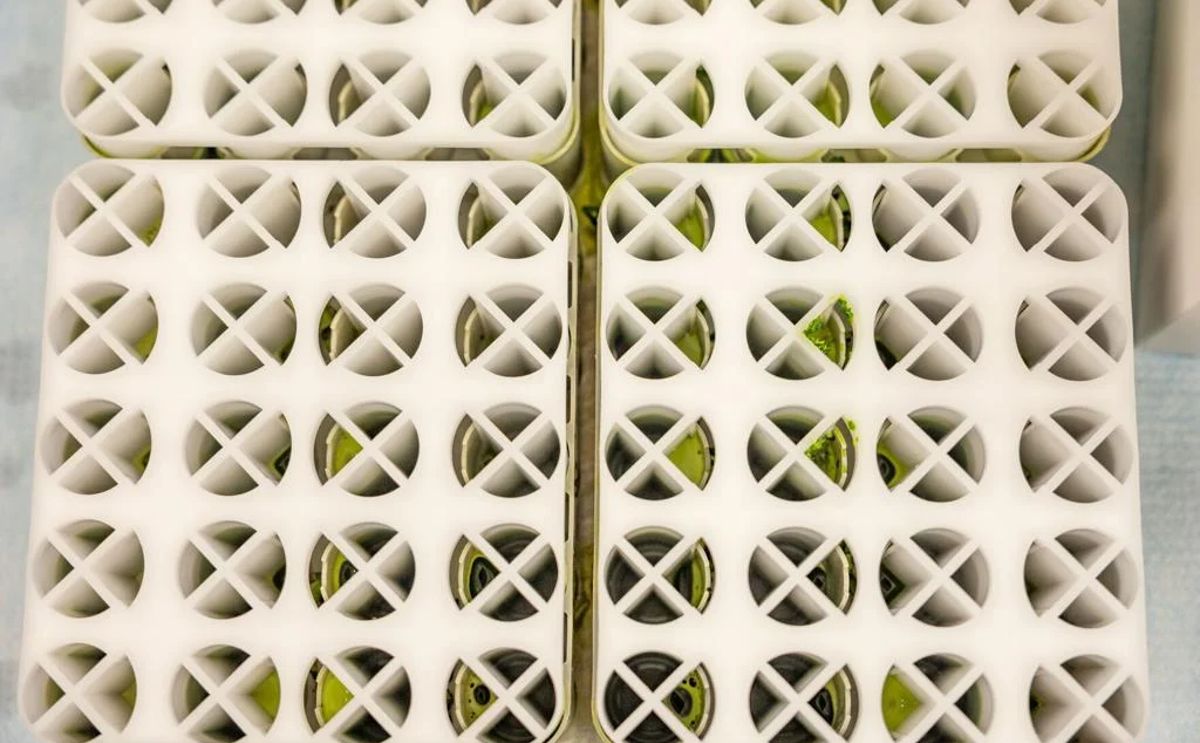

The Kimm field is planted with first generation, or G1, potatoes. For G1 fields, a flag sits between every ten potato plants. Pickers take a leaf from each of those ten plants to make one sample. They put the leaves into a box with a tray that has 80 wells, with 10 leaves going into each well.

Montana State University employees prepare to collect potato leaf samples at Kimm Seed Potato Farm on July 12, 2022. Courtesy: Ridley Hudson/ChronicleWalker Vanhouten, lead picker for the potato program, oversees the work of all pickers in the field. His job involves making sure people have the correct boxes and labels, and trying to prevent burnout. One week in early July the team worked two back-to-back 15 hour days, Vanhouten said.

Moriah Schutt, a Montana State University student, places potato leaf samples into a testing container on July 12, 2022 at Kimm Seed Potato Farm. Ridley Hudson/ChronicleThe team started picking on July 1 and will work until the first or second week of August. At this point in the summer, each person averages 8,000 leaves per day, Vanhouten said.

Walker Vanhouten, lead picker for the potato program:

“There’s a lot of work each day, but the season is pretty short.”

The flags in the field are numbered to match each sample box. For example, a box is labeled with the field location and what row numbers and flag numbers correspond to the samples inside.

Potato leaf samples fill boxes on July 12, 2022 at Kimm Seed Potato Farm. The samples will be tested for diseases. Ridley Hudson/ChronicleThat way, when the potato lab does test on each sample, if a disease is present, MSU can call the grower and tell them exactly which plants in the field are infected, down to the row and flag number spaced every ten plants.

Then growers can pull those plants and the surrounding ones to stop the spread of disease, Zidack said.

Zidack said that last year, the program monitored 11,303 acres of seed potatoes across Montana and picked two million leaves. Over time, the rigorous testing can decrease the amount of disease by providing farmers with data to inform their farm management practices.

Nina Zidack:

“Potatoes that are second generation are monitored in the field through a less rigorous process. Pickers gather a random, smaller sample of leaves, but there are no flags in fields after G1. Testing for generations three to five is optional, and after the fifth generation, seed potatoes are phased out of the program.”

Moriah Schutt, an MSU student in the sustainable food and bioenergy systems program, is part of the field crew this summer.

As she walked up and down rows plucking potato leaves for her sample box, Schutt carried a camelback in her daypack and wore a wide-brimmed hat she sometimes soaks with water to stay cool in the sun.

Schutt said the job can be “a little grueling,” with long days under the sun. But she said the work is satisfying, she’s making good money, and getting valuable work experience. Her favorite part about the experience is “being involved in a program you can’t find anywhere else”.

Moriah Schutt, an MSU student in the sustainable food and bioenergy systems program:

“The seed breeding program and research is not something other universities really have. The work will become faster-paced over the summer.”

On Monday, she filled 8.5 boxes with potato leaves — each box has 800 leaves in it — but on Tuesday she was expected to complete eight boxes before lunch.

Moriah Schutt:

“The work should get easier throughout the summer, as the potato plants grow taller. The taller the plant the fewer people have to bend down to pick the leaves.”

She’s averaging 37 minutes per box this week, compared to last week when it took her about 55 minutes for each box.

Moriah Schutt:

“It’s not easy money.”

Following picking, the leaf testing takes place in the MSU potato lab, which is also filled with student workers in the summer.

First, students take the sample boxes from the fridge, where they are stored in the lab until they are ready for processing.

Lab workers spray the trays with a buffer solution and then press the leaves in the tray with a machine called a plunger.

The press turns the leaves into a green potato-leaf liquid.

Potato leaves after being pressed into juice on July 14, 2022. Ridley Hudson/ChronicleThen, workers use a pipette to transfer the liquid to what is called an ELISA plate. Each well in the ELISA plate has antibodies for the virus tested for, mainly Potato Virus Y (PVY).

If the virus is present in a sample, it will bind to the antibodies and change color to yellow in around 30 minutes.

When the plate is washed out, yellow juice will remain in the samples where a disease is present.

Santo Mallon, Montana State University student, fills an ELISA plate on July 14, 2022 at MSU’s potato lab. Ridley Hudson/ChronicleZidack compared the process to a COVID test. Many at-home COVID tests start with one line, or the control for the test. When you swab your nose for the virus, if COVID is present in the sample, another line will appear on the test.

If it’s not present, nothing will happen, leaving just the one control line. The leaf juice changing color in the ELISA plate is a comparable process.

Eleanor Wagner, University of Denver student, works in Montana State University’s potato lab on July 14, 2022. Ridley Hudson/ChronicleZidack said the hands-on experience students gain both in the lab and field is a great benefit of the program. She is grateful to have a team of students who work hard and provide a critical service to Montana agriculture producers.

Megan Steinmasel, left, and Santo Mallon, Montana State University students fill ELISA plates with potato leaf juice to be tested for disease on July 14, 2022 at MSU’s potato lab. Ridley Hudson/Chronicle.

A source: https://www.potatopro.com