What’s wrong with my potato crop? Getting to the bottom of that question involves diligence and knowledge. These symptoms were caused by lygus bugs. If you lift the plant and look at the stem, you can see the scars where lygus bugs have been feeding with their piercing-sucking mouthparts.

When diagnosing problems in the farm field, it helps to think of yourself as a crime scene investigator looking for clues and establishing a timeline of events.

Be open-minded

There can be different causes for similar symptoms. For example, rolled and stunted leaves with purple margins and yellowing can indicate zebra chip disease, lygus bug feeding injury, stepping on the plant, and more. Why? The damage at a functional level is the same. They all restrict carbohydrates and pigments moving from the leaves to the rest of the plant, either by blocking the phloem or by physically damaging phloem cells.

Thoroughly examine affected plants

Look for abnormalities and note which parts of the plant are affected. Nutrient deficiencies can be difficult to diagnose, but the location of the symptoms on the plant can help you narrow down the options. Nutrients that move freely through the plant in both the xylem and phloem (e.g., nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, magnesium) usually show symptoms on older, mature leaves. That’s because the plant remobilized these nutrients via the phloem, from old leaves to the new — i.e., they sacrifice old growth for new.

That doesn’t happen with nutrients not moving in the phloem (e.g., calcium, iron, zinc). So when the plant starts to run out of these nutrients, you can find the symptoms on new growth. Look for signs of pests or pathogens, physical evidence like fungal mycelia and spores, insects and their droppings, webs, etc. They can be great clues but be careful not to mistake secondary pests as the initial cause.

Submit plant samples to a diagnostic laboratory for closer inspection.

- Collect plants with symptoms that aren’t masked by decay or secondary problems. Collect as much of the plant as possible. Include healthy plants for comparison.

- Put the samples in plastic bags, or in paper bags if sending fleshy material like potato tubers. Don’t add water. Put everything in a sturdy box and keep it cool until sending.

- Fill out a sample submission form and let the lab know when to expect your shipment.

- Ship ASAP. Next day arrival is best, except when it would get there on the weekend when the lab is closed.

Look for patterns in the field

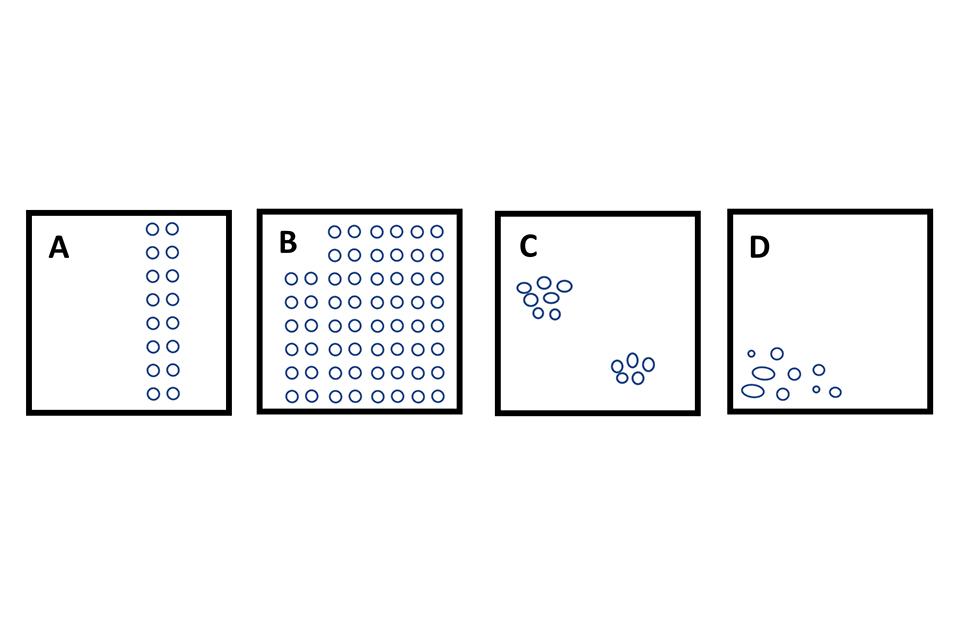

As shown below, symptoms that result from non-living causes (mechanical, chemical, nutritional, environmental, etc.) tend to be uniform across affected plants and appear in linear (A) or regular patterns (B) in the field. Symptoms from living causes (pathogens, insects, etc.) are almost always varied, with some plants showing more advanced symptoms than others, occurring in irregular patterns in the field. Diseases like late blight, Verticillium wilt, and nematode or wireworm damage create hotspots (C). Insect pests that tend to work their way in from the edge of the field (e.g., Colorado potato beetles, leafhoppers, and potato psyllids) naturally create symptoms that start near the field border (D).

Establish a timeline

Did the symptoms appear suddenly or gradually? Are the symptoms spreading? Symptoms caused by weather (e.g., hail, lightning, wind) or application mistakes (e.g., herbicide drift, spray tank residues) usually appear immediately or shortly after the event. And they do not spread to other plants afterwards. Symptoms caused by living factors tend to appear gradually. Most diseases and insect-related problems spread from plant to plant, sometimes slowly (e.g., wireworms) and sometimes rapidly (e.g., late blight).

Compile information

Take note about soil characteristics, crop inputs, and weather conditions leading up to symptom discovery. Are the plant’s nutritional needs being met? Could a mistake have been made with an application (e.g., wrong use rate, spray tank residue)? What were the prevailing weather conditions? Did the weather suddenly change? Plants growing in cool and cloudy conditions tend to produce leaves with a thin and clear cuticle. They are tender and can be damaged when it suddenly becomes hot and sunny, or very windy, or cold.

Consider field history

Was anything applied the previous season that could affect the plants now? Many herbicides can persist in the soil long enough to damage potatoes planted the following year (e.g., Arsenal, Pursuit [BASF], Banvel [Arysta LifeScience], and Stinger [Corteva Agriscience]). Carryover problems are more likely to occur when you use a high rate of herbicide, apply herbicide late in the season, or where environmental conditions (e.g., drought) or soil characteristics (e.g., low organic matter, coarse soils) result in slow chemical breakdown.

Were there problems with potatoes or other crops grown in the field previously? Soilborne diseases and damage from nematodes or wireworms are likely to recur if they caused problems in the past. It’s difficult to eradicate them entirely, even with soil fumigants and other interventions. Soil quality problems (e.g., sodic soil, saline soil, pH extremes) tend to show up no matter what crop is grown, if the soil conditions have not been improved.