Non-vascular bryophytes live in colonies that cover the ground and resemble tiny forests. In a real forest, plants compete for light in different layers of the canopy. If a plant does not receive enough sunlight, it stops lateral branching and instead grows vertically to reach the sunlight.

Researchers from the Gregor Mendel Institute of Molecular Plant Biology (GMI) of the Austrian Academy of Sciences discovered that the liverwort Marchantia polymorpha, whose plant body is fundamentally different from those of vascular plants, also adapts its architecture in response to shade. These new insights into the evolution of genetic pathways governing branching were published in Current Biology.

Forests are made of multi-layered canopies in which trees and other plants compete for light. Insufficient sunlight leads plants to regulate their branching patterns to favor vertical growth. Plants perceive the difference between direct sunlight and shade through phytochromes, photoreceptors that are universally present in the plant kingdom, from algae to bryophytes to flowering plants.

“We have long known that phytochromes inform vascular plants to stop growing laterally and instead grow vertically to avoid or outgrow a shading neighbor,” says the first author Susanna Streubel, a former postdoctoral fellow in the Dolan group at GMI. New branches along the stem are produced from the lateral meristems, the generative centers of plant stem cells that favor lateral growth. “This response to shade requires that the activity of lateral meristems is shut down.”

Liverworts reduce branching in the shade

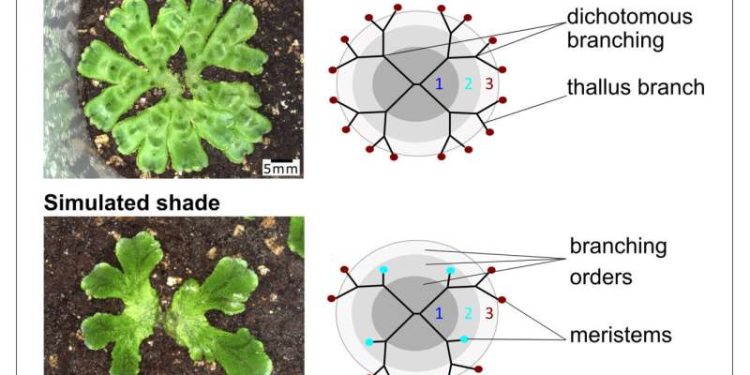

The researchers hypothesized that liverworts, non-vascular bryophytes that are presumed to resemble the earliest land-colonizing plants, also have a mechanism to adapt their branching pattern to changing light conditions. Like vascular plants, they have meristems and are capable of branching. However, in contrast to vascular plants that branch laterally below the tip or apex, bryophytes only branch at the apex in a mechanism called dichotomous branching.

The researchers phenotyped liverworts and found that in full white light, the flat liverwort body, also known as the thallus, branched regularly. “In the simulated shade, however, many liverwort meristems along the main axis of growth became dormant and did not produce branches. Thus, the thallus expressed features of shade avoidance,” says Streubel. As liverworts also use phytochromes, the researchers analyzed mutations affecting phytochrome and phytochrome-associated genes. They demonstrated that similarly to vascular land plants, the phytochrome signaling pathway guides the shade-avoidance response in the liverworts.

Independent evolution of molecular regulation?

Dolan and his team searched for additional genetic regulators of dichotomous branching and meristem activity in M. polymorpha. By examining patterns of gene expression in full white light vs. shade, they discovered that a transcription factor called MpSPL1 and a liverwort-specific microRNA (miRNA) have antagonizing effects on meristem function: MpSPL1 is essential for rendering meristems dormant, whereas the liverwort-specific miRNA activates them.

These results partly contrast with the known molecular mechanism of light-regulated lateral branching in Arabidopsis thaliana, the most studied model of vascular plants. In fact, although the genes controlling light-regulated branching in Arabidopsis also belong to the SPL family and are targets of miRNAs, they are evolutionarily distant from those now identified in the liverwort.

With these results, the team speculates that the molecular mechanisms regulating branching might have evolved independently in bryophytes and vascular plants. “Overall, our findings demonstrate that a partly conserved mechanism of phytochrome-regulated miRNA and SPL gene activity controls branching in completely divergent families of land plants with fundamentally different modes of branching,” says the GMI Group Leader Liam Dolan, the corresponding author of the study.