Soil moisture levels can have a huge effect on how your potato yield and quality.

Because of its shallow root system, the potato crop is sensitive to drought. High yields of high-quality potatoes can only be achieved by maintaining adequate levels of available soil moisture throughout the growing season. Without regular rainfall, frequent irrigation is necessary. Climate change will alter rainfall patterns and temperature, which will affect potato growth as well as the incidence of diseases and pests. Drought stress has a tremendous impact on potato production and its impact depends on the severity and duration of the stress and on the crop growth stage as well.

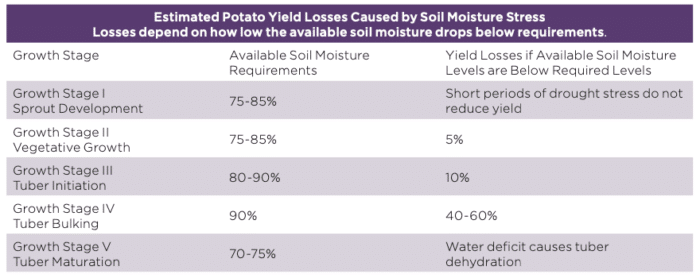

The table below shows the growth stages and the amount of available water required for a high yield of high-quality potatoes. Soil moisture should be above 70 per cent for all stages — stress becomes critical when the available soil water drops below 65 per cent.

Research in the United States has shown yield losses will occur if available soil water drops below required levels for more than five days. The first response of potatoes to water stress is the closure of leaf stomata, the small pores that control gas exchange between internal leaf cells and the environment. This is a defense against further water loss, but it also restricts the diffusion of carbon dioxide into the leaf. This slows photosynthesis, reducing the production of the sugars needed for tuber growth, which lowers yield and quality.

Water deficits at tuber initiation reduce tuber set and can increase the proportion of rough, misshapen tubers. Early-season water stress can also reduce specific gravity and increase the amount of jelly-end rot. Water stress during bulking disrupts tuber growth by reducing or stopping tuber expansion. When tuber growth resumes after rain or irrigation, the result is misshapen tubers with cracks, pointed ends and knobs. Water stress during bulking affects total yield more than quality. Tuber bulking slows down for maturation and soil moisture can be reduced. Excessive irrigation will cause soft rot, Pythium leak and enlarged lenticels.

Mechanical damage at harvest is affected by soil water content. Dehydrated tubers are more susceptible to blackspot bruising. After a period of moisture stress, potatoes need time to recover some or all their physiological functions. Consequently, the effect on tuber yield may be considerable. Research has shown that plants do not recover fully after severe moisture stress for seven days.

The good is balanced with the bad for potatoes. The stages of growth that’s most affected by heat stress are tuber initiation, vegetative growth and tuber bulking. When the temperatures are high and there’s more respiration, dry matter distribution favours developing foliage and so tuber dry matter suffer, and they can get unacceptably low especially for the processing industry. With the warmer temperatures, pests and weeds can overwinter become more productive, more invasive, and multiply faster.

It should not be news to anybody that increasing the organic matter level of our soil is associated with increasing the water holding capacity, helping to buffer changes in soil temperature and keep soil cooler. It also helps foster a healthy microbiome that suppresses disease and cycles nutrients.

There are few management strategies for dealing with water shortages other than irrigation.

- Increasing soil organic matter to three to four per cent mitigates moisture stress by improving water-holding capacity. Manure and cover crops help increase the organic matter in soils.

- Pick varieties that develop a large canopy rapidly to shade the soil and reduce water loss. This isn’t always possible given the demands of the market.

- Good calcium nutrition is important to reduce the impact of stress, not just water stress.

As always, Mother Nature is in charge; growers should hope for the best but prepare for the worst.