(NOTE: This is the first of a two-part series on the Vision 2026 program to rethink the seed potato certification system.)

A crop consultant’s persistence to help seed potato growers and belief that there was a faster and better way to get seed health data provided a perfect backdrop for researchers from USDA-ARS (Ithaca, New York) and Colorado State University (CSU) to translate a decade-long lab-based work into real world use. Interestingly, this stakeholder-driven effort merged well with the National Potato Council’s Vision 2026, a group tasked to recognize and use new tools available to produce higher quality potatoes to meet the demands from consumers as margins get tighter.

A system with over a century-old history

Seed potato certification in the U.S. has a history of protecting seed potato health since 1913. Certification agencies and researchers have determined which pathogens are important, developed sensitive molecular tests for nearly all pathogens that limit U.S. seed potato production, and developed appropriate sampling and tolerance levels for tuber-borne diseases.

Current seed potato certification relies primarily on visual inspection of potato fields during the growing season followed by postharvest grow outs for detecting viruses, such as PVY. Collectively, the 16 state-level seed potato certification programs evaluate 100,000 acres in the summer and further sample over a million tubers from those fields annually to evaluate the health of seed lots in winter testing systems.

Need to adjust the status quo

So, if everything is in place, one may be wondering whether there is a need to revisit the current methods. Well, continuous reliance on visually identifiable symptoms has provided a form of selection pressure for pathogen strains that lack easily observed symptoms. In addition, global movement of germplasm is responsible for the introduction and dissemination of other emerging pathogens that are novel or changed since seed certification was originally implemented. Several new pathogens, such as potato mop-top virus and tobacco rattle virus that can cause processor rejection from internal defects, are poorly understood. These new pathogens may express foliar symptoms differentially based on climate, potato cultivar, and latitude and some rarely cause any foliar symptoms.

Timeliness for making critical business decisions

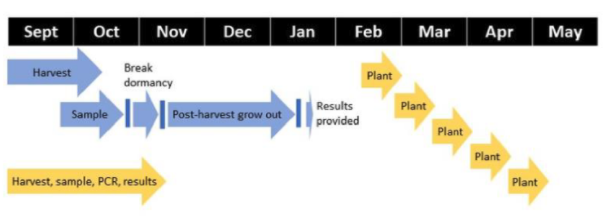

Most importantly, seed potato certification agencies typically provide certification results to growers four months after harvesting tubers. This involves collecting sample tubers, chemically breaking tuber dormancy, shipping several thousand pounds of tubers to winter grow out locations such as Hawaii and Florida, sampling leaves from vines, testing and then providing results to growers. This time lag limits seed potato grower and seed buyer ability to make sound business management decisions as they wait for seed certification results that decide whether the seed could be sold as a certified seed or not.

To provide a commitment to a prospective seed potato buyer, the seed potato grower should be able to get certification results at the earliest possible time. One way to overcome this bottleneck is to use PCR testing (similar to a SARS-CoV-2 virus test) on newly harvested tubers that can improve pathogen detection while providing expedited results to growers.

This made sense to Don Sklarczyk, who is tasked with investigating the industries future needs as the volunteer chair of the National Potato Council’s seed potato health initiative Vision 2026 Committee. Sklarczyk himself, an innovator in tissue culture potato production in the 1980s at Sklarczyk Seed Farm, Michigan, has walked the line between economy of efficient production vs. the risk/benefit of new methods and this experience made Don an obvious choice to coordinate groups seeking new ways to do things.

How it all started

What started out in Stewart Gray’s (retired USDA-ARS scientist) lab as a request to “find a way to test tubers for potato viruses and be able to test them by the 10,000s” has since developed a life of its own with interest across a variety of states and certification agencies. Tuber testing on the scale needed to certify a seed lot can be a measure of human stamina because it requires 400 randomly collected tubers to predict whether disease levels are acceptable in the entire field.

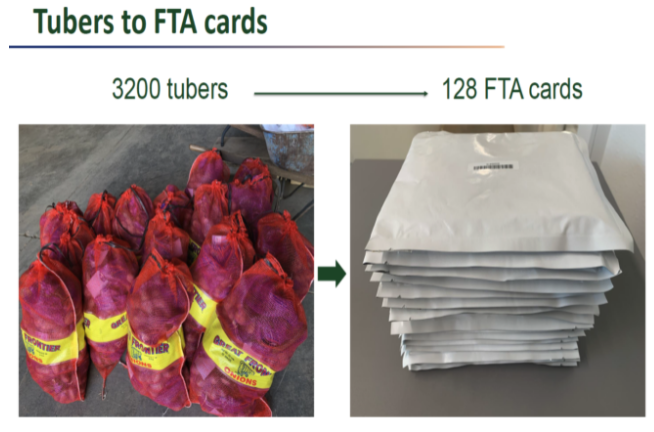

But how do you test tubers by the thousands? Gray’s lab adapted police crime scene technology with the development of a customized version of Whatman FTA Cards that are common in human testing. This new method provided a safe and reliable way to collect, transport and store potato DNA at room temperature. This approach also eliminated the need to ship heavy tubers covered in dirt to testing laboratories. Further, they developed molecular assays for large scale processing and figured out the type of sample that must be taken from a tuber to have acceptable statistical odds to determine the true infection status. Now that the methods were developed, the next logical step was to put these methods into real-world applications.

Many hands make work light

Learning about Gray’s research, a progressive seed grower interested in learning more about his farm’s seed potato crop teamed with USDA-ARS and CSU researchers and offered his farm, labor, and seed crop as an experimental site for on-farm collaboration. In October 2020, the grower committed his field roguing crew for two days of paid labor for tuber sampling — handling tubers being one of the barriers to lab-based molecular testing.

The crew were trained onsite to place tuber samples on FTA cards that were shipped to a USDA-ARS lab for downstream analysis in lieu of shipping tubers. In return, the grower received a competitive advantage with early results about his seedlots in November as compared to the existing standard of February results from the winter grow-outs.

What was learned

Collectively, the team gained valuable insight that this project has some “how to” components that must be addressed for scalability. When the results were presented to the seed grower cooperator, there was a discussion that supported the need for a larger dataset involving cooperators from different states and seed lots so data with higher confidence could be obtained. The experiment has been repeated with 2021 harvested seed lots and additional seed growers from Idaho, Colorado, Nebraska and Washington. Those growers had all received their own confidential seed test results for PVY, PMTV and TRV by Nov. 18 this year and are awaiting the results from grow-out tests of those tubers for comparison.

On the horizon

The NPC Vision 2026 program seeks ultimately to allow the potato industry to use the latest high-throughput testing technology, some developed because of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and its variants. Vision 2026 members are actively seeking partners to do so. This seed grower driven-project to develop a farm and lab model for adoption of commercial high throughput PCR-based seed potato testing as well as identify and mitigate barriers for wider scale adoption of this approach is perhaps what the NPC envisioned.

Anticipated seed potato grower participation in this project driven by the prospects of obtaining results faster than conventional winter grow outs is expected to boost the acceptance of this new approach by the potato industry in the U.S. Alternatively, transitioning to a high throughput molecular-based diagnostic will collectively provide the potato industry with faster, more accurate seed health data, which should improve future quality and hopefully improve commercial crop trade security.

We’re proceeding with caution, however. This decade-long grower-driven approach to develop and bring this method up to scale should guard against over-regulation and over-testing of seed potatoes, all while allowing for flexibility to respond to emerging diseases.