Thanks to a collaboration between researchers across the world, including the Alliance of Bioversity International and the International Center for Tropical Agriculture, potato breeders will now have a much better toolkit to develop new varieties best suited to their needs in a changing climate.

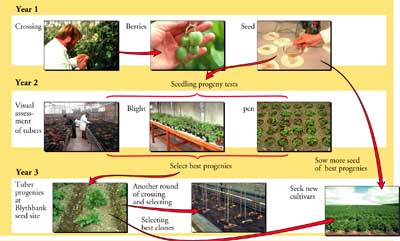

Over 1.3 billion people eat potatoes as a staple food, making it the third most important food crop after wheat and rice, but the way that potatoes reproduce means that new cultivars can take up to 40 to 50 years to come to market. Researchers based in Hawaii, the U.S. mainland and London found it is critical for breeders to have access to the best information possible to make informed decisions about which breeding strategies will lead to the desired traits needed in a changing climate.

In their Food and Energy Security paper “Wild relatives of potato may bolster its adaptation to new niches under future climate scenarios,” the researchers say that up to 12.5% of the current cultivated potato climate will shift into novel regions by 2070. “But if we want to have something new by 2050, we need to make the decision by 2030,” said Michael Kantar, an assistant Professor at the University of Hawaii and one of the co-authors of the paper.

Kantar explains that by identifying useful traits — like local adaptability and climate flexibility — in some of the dozens of wild varieties of potatoes (and how well they interbreed), researchers could help breeders cut down on the time and cost to develop new cultivars. “Traditionally, if you have 72 potential species of potatoes and then take 10 samples and cross them back to your favorite cultivar, then you would assess in multiple regions — that’s a lot of time and cost,” he said, adding that starting with knowledge what crosses might successfully crossbreed would cut down on the number of trial plants needed.

Nathan Fumia, a researcher at the Department of Tropical Plant and Soil Science, University of Hawaii in Honolulu and another coauthor on the paper said most potatoes, wild and domesticated, have been sequenced in some way. Another paper, also authored by Fumia, called “Interactions between breeding system and ploidy affect niche breadth in Solanum” was published in Royal Society Open Science and looked at a wide range of potato species and their phylogenetics, that is, the evolutionary history and relationships among individuals or groups of organisms.

“By looking at phylogenetics we were looking for a proxy for if it can be interbred: if it is more closely related, it is more likely it can be interbred,” Fumia said. Fumia and his coauthors found that decoupling geographical range and niche diversity, would help identify species that may be of particular interest for crop adaptation to a changing climate.

“That was something we saw was missing in the literature and this was the framework for what we looked at in the other paper,” he said. Kantar says that rather than imposing new breeds on new regions, the genetic data analyzed by the researchers can help provide useful information to make local breeding easier. “What we want to do is give them a tool about their own conception about how they want their own food system to work,” Kantar said.

Colin Khoury, a co-author on both papers and a researcher at the Alliance of Bioversity International and the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), and Director of Science and Conservation at the San Diego Botanic Garden, said CIAT ‘s role has been in long time research into the wild relatives of crops and in particular understanding their conservation status through the use of geospatial tools.

Khoury explained that Kantar worked at CIAT as a postdoc and trained with the organization in the use of these tools and methods. “This carries on in his current work as seen in the two papers just published and we continue to collaborate with the Kantar lab and have been happy to help mentor their students,” Khoury said.

“Both of these papers develop new methods or use ever more pertinent data related to the usability of wild relatives for crop breeding,” he said adding that one uses information about their genetic systems and reproductive strategies; and the other by better understanding their ecological niches in reference to the likely growing areas of the potato crop in the future.

“These both provide extra value regarding what wild relatives may contribute to crop improvement.”