The International Potato Center (CIP) has substantially contributed to the development and release of improved potato varieties that are grown by millions of farmers in Asia’s top potato producing countries.

CIP says in this news story that it contributed to 34% of total releases of improved potato varieties in the region, and an adoption assessment completed in 2015 estimated that CIP-related varieties were planted to more than 1.45 million hectares (19% of the total potato area in the seven countries studied), grow by 2.93 million farming households, and benefited more than 10 million people.

Key traits such as late blight and virus resistance, relatively rapid development of tubers, and tolerance of heat, drought or saline soils have made CIP-related potato varieties increasingly important for smallholder farmers, helping them overcome challenges such as limited land and climate change to produce more food and generate more income.

These varieties have boosted food security and incomes across the region. In China, the world’s top potato producer, CIP-related varieties are grown on about 25% of the land dedicated to the crop.

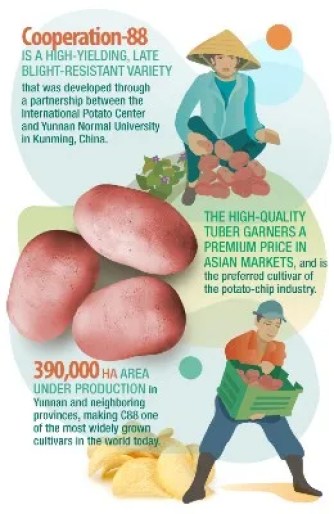

The most successful is Cooperation 88 (C88), the result of collaboration between CIP and Yunnan Normal University. A late blight-resistant variety, it has excellent qualities for both home consumption and processing, all of which contributed to widespread adoption by farmers. Estimated economic benefits from C88 between 1996 and 2015 range from USD 2.84 to a USD 3.73 billion in Yunnan province alone.

Climate-smart potato varieties in Asia

Across Asia, 170 potato varieties have been released either through the International Potato Center (CIP)’s breeding program over the last four decades, or by using germplasm held in its collections.

These varieties are bred to be climate-smart, to mature, and to help fight off potato pests and diseases, contributing to the food and nutrition security, and the livelihoods, of 10 million people across Asia.

Potato is one of the most important crops in Asia where farmers produce 96 million metric tonnes (or 53 million Volkswagen Beetles) of potatoes annually, a number that has increased by 50% over the last ten years in the seven most important Asian potato-growing countries – Bangladesh, China, India, Indonesia, Nepal, Pakistan, and Vietnam.

This success is largely due to the use of improved potato varieties, including those that come from CIP’s breeding program. Today 20% of the land with potatoes across the seven countries is planted with CIP varieties.

“Across Asia, the effects of climate change increase longer drought spells and pest and disease outbreaks. says Marcel Gatto, an agricultural economist from CIP based in Vietnam. “This means that we need to breed more climate-smart varieties that can resist existing and novel diseases and that can work in different local conditions. We also need to continually find ways to speed up the breeding process so that we can make new and preferred varieties available to farmers as quickly as possible.”

So far, nearly 3 million farming households across these seven countries are cultivating CIP-related varieties.

Precocious varieties take the heat in Bangladesh and India

“We have seen a high take-up rate for our precocious potatoes. These are the ones that mature early and are climate-smart so reduce farmers’ risk of crop failure and income loss,” says Guy Hareau, Leader, Social and Nutritional Sciences Division, CIP. “In Bangladesh, using precocious varieties to sustainably intensify rice agri-food systems could result in economic gains of around $80 million per year, while in India, precocious varieties like Kufri Lima, are helping to secure harvests and livelihoods in increasingly hot temperatures.”

“Earlier planting means earlier harvests and a premium price at the market. Wheat and rice farmers can also plant an extra crop during the fallow period which was once considered too hot to grow potatoes,” adds Samarendu Mohanty, CIP’s Regional Director for Asia.

Drought-loving varieties in Central Asia

Climate change is also increasing the risk to potato harvests posed by drought. Farmers in Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan already face severe droughts on average once every five years, which according to climate modeling, are predicted to increase in frequency, severity, and duration. CIP has worked with the National Agricultural Research Systems (NARS) in Central Asia for several decades to help farmers produce better harvests with less water, developing varieties like UNICA that combine stress resilience with faster production to reduce water consumption.

“Introducing drought-tolerant varieties also means that potato production can extend into new areas increasing the number of families who will benefit from them,” says Rusudan Mdivani, CIP’s Regional Leader for Central Asia. “For example, UNICA grows well in both mountains and lowlands, making it ideal for the local conditions, and it is resistant to potato viruses which is also a huge challenge for farmers.”

Beating late blight disease in China

In China, where CIP-related varieties cover 25% of the land planted to potatoes, Cooperation 88 (C88) is helping farmers to beat late blight disease. Late blight costs the global economy up to $10 billion annually in yield loss and agrochemical use. Between 1996-2016, high-yielding C88 has contributed up to $3.7 billion to the potato economy in Yunnan alone and is one of the most planted CIP varieties in the world.

“The main reason that C88 is so popular with farmers is its resistance to late blight,” continues Hareau. “Farmers that grow it have seen yield increases of around 15% and as it is also popular with consumers, which in turn, boosts farmer incomes and provides more incentives to grow it.”

Looking ahead

“The high adoption rates we have seen across Asia validates the decades of work by breeders using genetic diversity conserved in the CIP genebank to develop improved potato varietiesv that meet the needs,” says Oscar Ortiz, CIP Deputy Director General for Research and Development.

“But the work does not stop here. We need to continue to deliver what farmers need in terms of growing traits, and also look at other benefits that potato can bring, for example to improving nutrition.”

The latest Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN (FAO) estimates that more than half of the people in the world affected by hunger are in Asia. South Asia is also home to high rates of micronutrient deficiencies such as iron, zinc, and vitamin A which the body needs for healthy development, particularly in young children.

“We are currently evaluating improved potato varieties that we have biofortified with iron and zinc in several Asian countries. When combined with our work to fill Vitamin A gaps with biofortified orange-fleshed sweetpotato, we see the potential that potatoes can make a difference to improving yields and incomes, and to reducing malnutrition across Asia,” concludes Ortiz.