Germination is a crucial stage in the life of a plant, as it will leave the stage of seed resistant to various environmental constraints (climatic conditions, absence of nutritive elements, etc.) to become a seedling that is much more vulnerable. The survival of the young plant depends on the timing of this transition. It is therefore essential that this stage be finely controlled.

A Swiss team, led by scientists from the University of Geneva (UNIGE), has discovered an internal thermometer of seeds that can delay or even block germination if temperatures are too high for the future seedling. This work could help optimize plant growth in the context of global warming. These results can be read in the journal Nature Communications.

Newly formed seeds are dormant; they are unable to germinate. After a few days (or even months, depending on the species), the seeds awaken and acquire the ability to germinate during the favorable season for seedling growth and new seed production. However, non-dormant seeds can still decide their fate. For example, a non-dormant seed that is suddenly subjected to excessively high temperatures (greater than 28°C) can block germination. This mechanism of repression by temperature (thermo-inhibition) allows a very fine regulation. A variation of only 1 to 2°C can indeed delay the germination of a seed population and thus increase the chances of survival of future seedlings.

A key protein: Phytochrome B

The group of Luis Lopez-Molina, professor at the Department of Plant Sciences of the Faculty of Science of the UNIGE, is interested in the control of germination in Arabidopsis thaliana, a plant species belonging to the Brassicaceae family and used as a model in many research projects. To understand the detection mechanisms that allow seeds to trigger thermo-inhibition, scientists explored the track of phenomena already described and quite similar in young plants (i.e., at a more advanced stage of development).

Indeed, seedlings also perceive temperature changes, where a slight increase in temperature promotes stem growth. This adaptation is similar to the one observed when a plant finds itself in the shadow of another: It lengthens to escape the shadow in order to expose itself to the sunlight, which is more favorable for photosynthesis. These variations are detected by a protein sensitive to light and temperature, phytochrome B, which normally acts as a brake on plant growth. An increase of 1 to 2°C promotes the inactivation of phytochrome B, which makes it less effective in preventing growth.

An internal thermometer

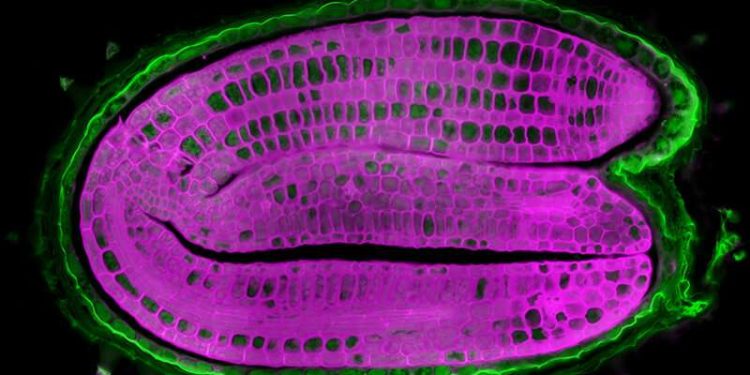

To understand whether phytochrome B also plays a role in thermo-inhibition during germination, the authors dissected the seeds to separate the two tissues inside the seed: the embryo (which will yield the young plant) and the endosperm (nourishing tissue that also controls germination in Arabidopsis seed). Unlike embryos grown in contact with the endosperm, the researchers found that embryos deprived of their endosperm are unable to stop their growth under excessively high temperatures, which leads to their death.

“We found that thermo-inhibition in Arabidopsis is not autonomously controlled by the embryo but implemented by the endosperm, revealing a new essential function for this tissue,” explains Urszula Piskurewicz, researcher at the Department of Plant Sciences of the UNIGE Faculty of Science and first author of the study. “In other words, in the absence of endosperm, the embryo within the seed would not perceive that the temperatures are too high and would begin its germination, which would be fatal.”

Optimizing crop germination

Thermal inhibition of germination is a new example of the influence of climatic variations on certain cyclic phenomena in plant life (germination, flowering, etc.). “This trait is expected to have an impact on species distribution and plant agriculture and this impact will be greater as temperatures increase worldwide,” reports Luis Lopez-Molina, the study’s last author.

A better understanding of how light and temperature trigger or delay seed germination could indeed help optimize the growth of plants exposed to a wide range of climatic conditions.