As a key input in food production, chemical fertilizers are crucial in reducing hunger and eradicating poverty over the past decades. However, using them has become a luxury for farmers in low and middle-income countries as fertilizer prices have soared over the past two years.

Earlier this month, the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) released its global food price index for September. FAO Chief Economist Maximo Torero pointed out that developing countries still face food problems even though food prices have decreased since March, and the increasing global fertilizer prices are more likely to reduce their crop yields next year.

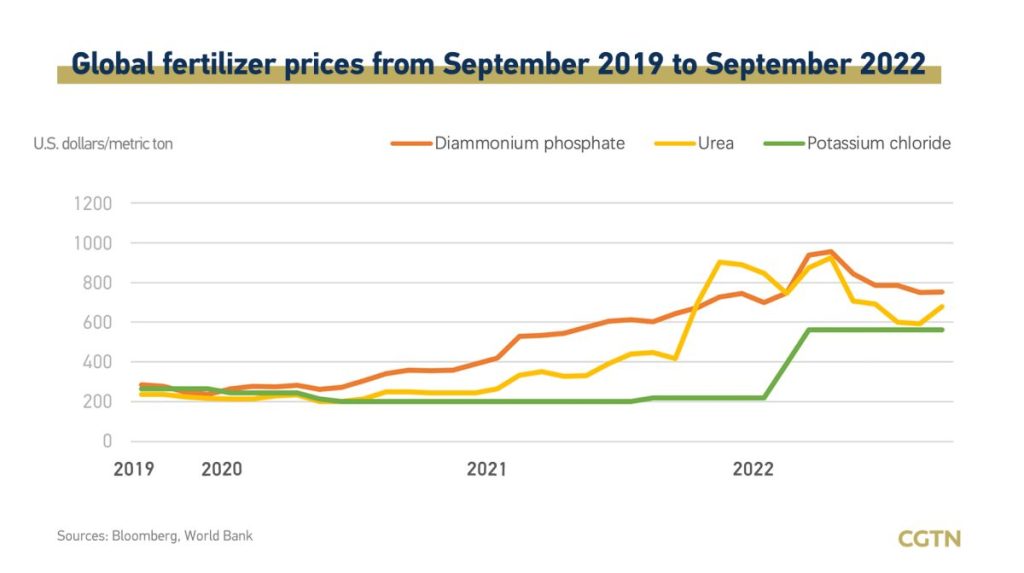

According to the World Bank, fertilizer prices in September this year climbed 6 percent. Compared to September 2021, the fertilizer price index has seen a surge of nearly 72 percent.

In addition to existing pandemic-related stresses, the Russia-Ukraine conflict has caused major shocks to commodity markets. The war has led to severe disruptions of the production and trade of fertilizers, for which Russia and Ukraine are key exporters, along with energy and grains.

As the war continues, fertilizer prices are expected to reach one of their highest points in history, after the 1973 oil crisis and 2008 financial crisis.

Western countries claim that the sanctions against Russia do not cover the production, sale and transportation of agriculture-related goods. But Russia said these sanctions have resulted in many obstacles in bank settlement, insurance and shipping, causing a large amount of Russian fertilizer to be grounded in European ports.

As fertilizer prices rise, making a living out of growing grains has become increasingly difficult for farmers. The consequences, especially for countries facing food insecurity, could be disastrous.

“All countries in South Asia are developing countries. Agriculture is a major driver in their economies and fertilizers have been a necessity to guarantee crop yields. Without fertilizers, they can hardly feed themselves,” said Li Qingyan, associate research fellow at the Department for Developing Countries Studies at the China Institute of International Studies.

Taking the recent economic crisis in Sri Lanka as an example, she said the country’s nationwide ban on chemical fertilizers last year crippled its agriculture, which increased the risk of repaying its debt.

Li added that most developing countries rely on imported fertilizers, and high fertilizer prices increased the cost of economic recovery in these countries.

More hunger and chaos

Last year, the number of people affected by hunger worldwide reached 828 million, an increase of 150 million since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a UN report released in July. Regional conflicts, extreme weather, soaring food prices, inequality and international tensions are all affecting global food security in 2022 as the COVID-19 pandemic continues. Developing countries have suffered the most in the worsening global food crisis.

Speaking at a ministerial conference on global food security in June, Indonesian Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi said the scarcity of fertilizers could bring disaster to 2 billion people in Asia.

Far away in Latin America, Brazil and Venezuela import about 80 percent of their fertilizers each year from Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. The fertilizer crunch has pushed their agricultural experts and farmers to seek alternative crops and soil nutrients. In June, the FAO organized a seminar on the use of biofertilizers in Brazil, Chile, Peru and the Caribbean.

The effects also extended beyond agriculture. In April, in response to protests against a spike in fuel and fertilizer prices, Peruvian President Pedro Castillo declared a state of emergency for one month and curfew in the capital city of Lima that was later withdrawn.

West Africa will face a fertilizer deficit of between 1.2 and 1.5 million tonnes if the Russia-Ukraine conflict persists, according to a report published by Economic Community of West African States in July. The region could experience a loss of cereal production of around 20 million tonnes, which accounted for more than a quarter of the production recorded last year.

The report recommends strengthening local fertilizer production capacity and distribution channels. But these production lines, which require large sums of investment, technology and equipment, can take years to build.

Brokered by the UN and Türkiye, Russia and Ukraine signed the Black Sea Grain Initiative in July, which reopened sea channels for exports of grain and fertilizer from three key Ukrainian ports in the Black Sea region. However, data shows that only about a quarter of agricultural goods from Ukraine went to low and lower-middle income countries, which was criticized by Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Last week, Russia expressed its concerns about the deal and said it is prepared to reject renewing it in November when the three-month initiative terminates, Reuters reported. The collapse of the deal could also worsen the global food crisis.

At a security meeting in September, Putin said Russia was willing to provide hundreds of thousands of tonnes of fertilizer sitting in European ports to developing countries in need of it, for free, according to Xinhua News Agency. But there are no concrete plans yet.

“For the last three years, hunger numbers have repeatedly hit new peaks. Let me be clear, things can and will get worse unless there is a large scale and coordinated effort to address the root causes of this crisis. We cannot have another year of record hunger,” said David Beasley, executive director of the UN World Food Program, ahead of World Food Day on October 16.

(Cover image: Harvesting rice in a village in Bogor, West Java, Indonesia, September 27, 2022. /CFP)

Text by Du Junzhi

Video edited by Yang Yiren

Info-graphic designed by Yu Peng