During the Seven Years War of the mid-1700s, a French army pharmacist named Antoine-Augustin Parmentier was captured by Prussian soldiers. As a prisoner of war, he was forced to live on rations of potatoes. In mid-18th century France, this would practically qualify as cruel and unusual punishment: potatoes were thought of as feed for livestock, and they were believed to cause leprosy in humans. The fear was so widespread that the French passed a law against them in 1748.

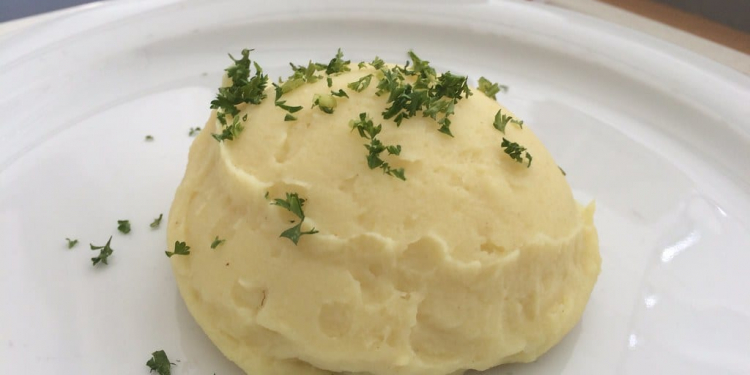

But as Parmentier discovered in prison, potatoes weren’t deadly. In fact, they were pretty tasty. Following his release at the end of the war, the pharmacist began to proselytize to his countrymen about the wonders of the tuber. One way he did this was by demonstrating all the delicious ways it could be served, including mashed. By 1772, France had lifted its potato ban. Centuries later, you can order mashed potatoes in dozens of countries, in restaurants ranging from fast food to fine dining.

The story of mashed potatoes takes 10,000 years and traverses the mountains of Peru and the Irish countryside; it features cameos from Thomas Jefferson and a food scientist who helped invent a ubiquitous snack food. Before we get to them, though, let’s go back to the beginning.

THE ORIGINS OF THE POTATO

Potatoes aren’t native to Ireland—or anywhere in Europe, for that matter. They were most likely domesticated in the Andes mountains of Peru and northwest Bolivia, where they were being used for food at least as far back as 8000 BCE.

These early potatoes were very different from the potatoes we know today. They came in a variety of shapes and sizes and had a bitter taste that no amount of cooking could get rid of. They were also slightly poisonous. To combat this toxicity, wild relatives of the llama would lick clay before eating them. The toxins in the potatoes would stick to the clay particles, allowing the animals to consume them safely. People in the Andes noticed this and started dunking their potatoes in a mixture of clay and water—not the most appetizing gravy, perhaps, but an ingenious solution to their potato problem. Even today, when selective breeding has made most potato varieties safe to eat, some poisonous varieties can still be bought in Andean markets, where they’re sold alongside digestion-aiding clay dust.about

By the time Spanish explorers brought the first potatoes to Europe from South America in the 16th century, they had been bred into a fully edible plant. It took them a while to catch on overseas, though. By some accounts, European farmers were suspicious of plants that weren’t mentioned in the Bible; others say it was the fact that potatoes grow from tubers, rather than seeds.

Modern potato historians debate these points, though. Cabbage’s omission from the Bible didn’t seem to hurt its popularity, and tulip cultivation, using bulbs instead of seeds, was happening at the same time. It may have just been a horticultural problem. The South American climates potatoes thrived in were unlike those found in Europe, especially in terms of hours of daylight in a day. In Europe, potatoes grew leaves and flowers, which botanists readily studied, but the tubers they produced remained small even after months of growing. This particular problem began to be remedied when the Spanish started growing potatoes on the Canary Islands, which functioned as a sort of middle ground between equatorial South America and more northerly European climes.

It’s worth pointing out, though, that there is some evidence for the cultural concerns mentioned earlier. There are clear references to people in the Scottish Highlands disliking that potatoes weren’t mentioned in the Bible, and customs like planting potatoes on Good Friday and sometimes sprinkling them with holy water suggest some kind of fraught relationship to potato consumption. They were becoming increasingly common, but not without controversy. As time went on, concerns about potatoes causing leprosy severely damaged their reputation.

EARLY MASHED POTATO RECIPES

A handful of potato advocates, including Parmentier, were able to turn the potato’s image around. In her 18th-century recipe book The Art of Cookery, English author Hannah Glasse instructed readers to boil potatoes, peel them, put them into a saucepan, and mash them well with milk, butter, and a little salt. In the United States, Mary Randolph published a recipe for mashed potatoes in her book, The Virginia Housewife, that called for half an ounce of butter and a tablespoon of milk for a pound of potatoes.

But no country embraced the potato like Ireland. The hardy, nutrient-dense food seemed tailor-made for the island’s harsh winters. And wars between England and Ireland likely accelerated its adaptation there; since the important part grows underground, it had a better chance of surviving military activity. Irish people also liked their potatoes mashed, often with cabbage or kale in a dish known as colcannon. Potatoes were more than just a staple food there; they became part of the Irish identity.

But the miracle crop came with a major flaw: It’s susceptible to disease, particularly potato late blight, or Phytophtora infestans. When the microorganism invaded Ireland in the 1840s, farmers lost their livelihoods and many families lost their primary food source. The Irish Potato Famine killed a million people, or an eighth of the country’s population. The British government, for its part, offered little support to its Irish subjects.

One unexpected legacy of the Potato Famine was an explosion in agricultural science. Charles Darwin became intrigued by the problem of potato blight on a humanitarian and scientific level; he even personally funded a potato breeding program in Ireland. His was just one of many endeavors. Using potatoes that had survived the blight and new South American stock, European agriculturists were eventually able to breed healthy, resilient potato strains and rebuild the crop’s numbers. This development spurred more research into plant genetics, and was part of a broader scientific movement that included Gregor Mendel’s groundbreaking work with garden peas.

TOOLS OF THE MASHED POTATO TRADE

Around the beginning of the 20th century, a tool called a ricer started appearing in home kitchens. It’s a metal contraption that resembles an oversized garlic press, and it has nothing to do with making rice. When cooked potatoes get squeezed through the tiny holes in the bottom of the press, they’re transformed into fine, rice-sized pieces.

The process is a lot less cumbersome than using an old-fashioned masher, and it yields more appetizing results. Mashing your potatoes into oblivion releases gelatinized starches from the plant cells that glom together to form a paste-like consistency. If you’ve ever tasted “gluey” mashed potatoes, over-mashing was likely the culprit. With a ricer, you don’t need to abuse your potatoes to get a smooth, lump-free texture. Some purists argue that mashed potatoes made this way aren’t really mashed at all—they’re riced—but let’s not let pedantry get in the way of delicious carbohydrates.

THE EVOLUTION OF INSTANT MASHED POTATOES

If mashed potato pedants have opinions about ricers, they’ll definitely have something to say about this next development. In the 1950s, researchers at what is today called the Eastern Regional Research Center, a United States Department of Agriculture facility outside of Philadelphia, developed a new method for dehydrating potatoes that led to potato flakes that could be quickly rehydrated at home. Soon after, modern instant mashed potatoes were born.

It’s worth pointing out that this was far from the first time potatoes had been dehydrated. Dating back to at least the time of the Incas, chuño is essentially a freeze-dried potato created through a combination of manual labor and environmental conditions. The Incas gave it to soldiers and used it to guard against crop shortages.

Experiments with industrial drying were gearing up in the late 1700s, with one 1802 letter to Thomas Jefferson discussing a new invention where you grated the potato and pressed all the juices out, and the resulting cake could be kept for years. When rehydrated it was “like mashed potatoes” according to the letter. Sadly, the potatoes had a tendency to turn into purple, astringent-tasting cakes.

Interest in instant mashed potatoes resumed during the Second World War period, but those versions were a soggy mush or took forever. It wasn’t until the ERRC’s innovations in the 1950s that a palatable dried mashed potato could be produced. One of the key developments was finding a way to dry the cooked potatoes much faster, minimizing the amount of cell rupture and therefore the pastiness of the end-product. These potato flakes fit perfectly into the rise of so-called convenience foods at the time, and helped potato consumption rebound in the 1960s after a decline in prior years.

Instant mashed potatoes are a marvel of food science, but they’re not the only use scientists found for these new potato flakes. Miles Willard, one of the ERRC researchers, went on to work in the private sector, where his work helped contribute to new types of snacks using reconstituted potato flakes—including Pringles.