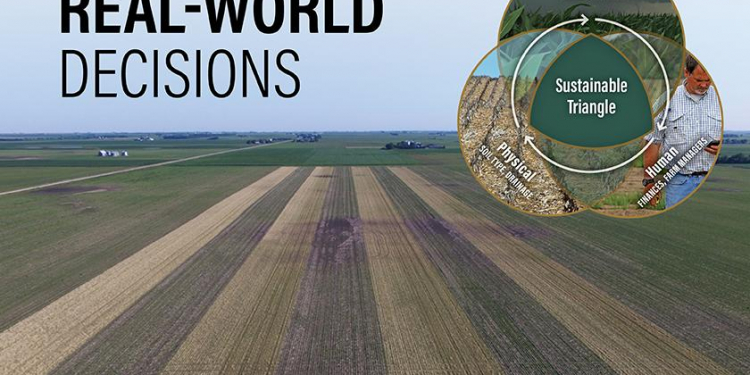

Evaluate cropping choices on physical, natural and human factors

Let’s see how two real farmers applied sustainable triangle principles to decisions about no-till and covers crops. Farm Journal Field Agronomist Ken Ferrie consulted with both farmers as they tested the two practices.

The sustainable triangle is where three environments overlap — the physical environment in each field, the natural environment (climate and weather) and the human environment (everything from profit to attitudes, both yours and your landlord’s). Meet the re-quirements of all three, and your farm will be profitable and sustainable.

Bringing Back An Abused Farm

FARMER 1, a successful no-tiller, was offered a new farm because the owner wasn’t satisfied with yields and wanted to improve soil health and reduce soil erosion. He explained to the owner the soil was too sick to no-till right away. Correcting all the problems would take several years.

PHYSICAL ISSUES:

- Serious compaction from years of shallow horizontal tillage.

- Low fertility, especially pH.

- Undecomposed residue that interfered with planting.

- Poor soil health, including low aggregate stability that led to crusting after 0.3″ of rain.

THE SOLUTION:

“Farmer 1 applied large amounts of lime in multiple applications,” Ferrie explains. “He incorporated it into the top 6″ using vertical till-age tools — a chisel plow in the fall and a vertical harrow in the spring. Two years of vertical tillage removed the compaction. But it took four to six years to fix the acidity problem. That didn’t surprise us because previous experience had shown it takes two or three years after you reach the correct pH for the soil to actually start handling better.”

By the sixth year, infiltration had improved, erosion was under control, residue was decomposing and yield had increased dramati-cally, Ferrie says.

“The grower could no-till most of the field, fixing areas with crusting issues with a vertical harrow pass before planting,” he says. “Seeing the potential, the landowner tiled some poorly drained areas.”

HUMAN FACTORS:

Landlords’ desires are part of the human environment. Farmer 1’s landlord thought cover crops could improve soil health even more. So after the first year of rehabilitation, he planted a cover crop.

- Two years of aerial seeding failed to produce a stand, due to weather conditions (the natural environment) and, possibly, less than optimal soil health (the physical environment).

- After eight years of rehabilitation, drilling cover crop seed right after harvest produced a great stand. Farmer 1 compared strips of no-till and covers against one pass with a vertical harrow before planting. “We killed the covers before soybean emergence, and the soy-bean stand was excellent,” Ferrie says. “But voles — absent in the vertical-harrowed strips — reduced the stand and yield in the cover crop strips.”

- Return on investment (ROI) also is part of the human environment. Cover crops had a negative impact on financial ROI. Now, Farmer 1 and the landowner must consider the “true ROI,” a term Ferrie coined to account for non-monetary rewards, such as job satisfaction and quality of life. Will the satisfaction of soil stewardship compensate for the cost of cover crop seeding and reduced yield (assuming no government incentives or carbon credit payments)?

Lessons From Eight Years Of Covers

FARMER 2 hoped no-till and covers would improve soil health and infiltration, helping water reach tile lines by creating biochannels. He laid out strips of cover crops versus his normal practice and kept them in place for eight years.

PHYSICAL ISSUES:

- Limited tile and moderate-to-poor drainage.

- Because of poor drainage, the field was late-planted and late-harvested, limiting the choices of covers that fit the planting window to oats, wheat, radishes and cereal rye. They were planted in various combinations ahead of corn and soybeans.

- Because prior experience with aerial seeding had been only marginally successful, Farmer 2 drilled the cover crop seed after harvest.

THE RESULTS:

“Cutworms showed up the first year, with damage in the cover crop but none 30″ away where Farmer 2 no-tilled without covers,” Ferrie says. “So cutworm scouting became a priority. The covers improved weed control, eliminating the need for a burndown treatment to control winter annuals. In the spring, killing the cover also controlled any weeds that were present. Soil biology and biodiversity improved but drainage did not.”

When wet spring weather precluded spraying the cover crop, and Farmer 2 had to plant in hood-high cover, the crushed mat of vegetation rendered his planter monitor completely ineffective. In that situation, Ferrie says, ground-truthing the planter is essential.

“Corn yield behind covers was reduced by 3 bu. to 10 bu. per acre every year,” he says. “Soybeans behind covers yielded the same as before or up to 2 bu. per acre less.”

HUMAN FACTORS:

Financial ROI is a concern. Without improvement in yield, Farmer 2 can’t offset the cost of the cover crop. He is moving away from covers, implementing strip-till and trying to persuade the landowner to install more tile.