Pathogen. This fungus persists in the soil for many years as tiny propagules called microsclerotia. Short crop rotations, especially in sandy soils with susceptible varieties, tend to increase the population of Verticillium to damaging levels. The fungus infects many other crops and weed species. High soil temperatures (22–27°C) favour the growth of this fungus.

Disease development. Microsclerotia of Verticillium germinate, and the fungus penetrates the plants through the roots. Once inside the plant, the fungus plugs the vascular tissue.

Symptoms. The first symptoms usually appear in early August in the lower portions of the plant. The area between leaf veins begins to yellow. Later, the symptoms move upward to the younger leaves. Leaf yellowing is followed by browning and necrosis. In early stages of the disease, not all the stems from the same plant show symptoms.

Infected plants wilt during the day but recover at night. The crop senesces early, 3–4 weeks before reaching maturity. As a consequence, tubers do not size and serious yield losses occur. The disease is favoured by crop stress induced mainly by heat, drought, nutrient deficiencies and insect damage.

The premature vine death and declining yields caused by Verticillium are called “potato early dying syndrome.” The root lesion nematode has been associated with this syndrome because it enhances the incidence and severity of Verticillium wilt.

younger leaves also turn yellow.

of the leaves turns yellow and wilts.

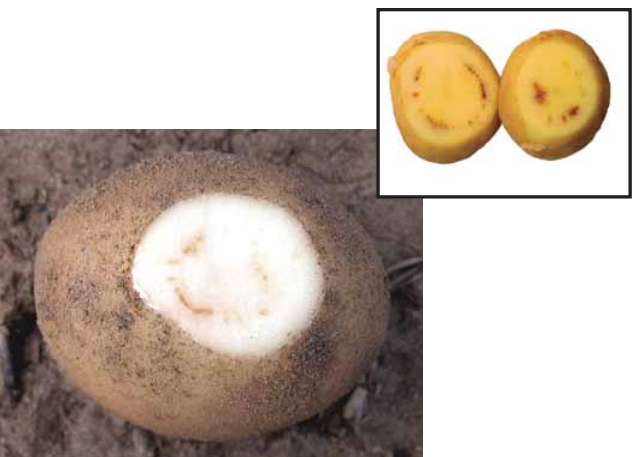

“woody tissue” of the stem. This symptom is

seen easily if the stem is cut close to ground

level with a long, slanting cut.

infested with Verticillium and the root lesion

nematode.

tuber. The discolouration does not usually extend more than halfway

through the tuber.