With more Americans eating their meals at home these days, many are interested in learning about how their food is produced, processed and distributed.

That requires openness on the part of farmers, according to Lucy Stitzer, founder of Dirt-To-Dinner, a blog focused on various food topics, including health and nutrition.

“The consumer wants not just abundance, but transparency too,” Stitzer says. “They want to know your story from start to finish.”

A March 2020 survey of 1,000 shoppers by the Food Marketing Institute (FMI) and Chicago-based Label Insight undergirds Stitzer’s perspective. The results show that a majority of consumers (81%) believe transparency is ‘important’ or ‘extremely important’ to them when shopping for food.

Ken McCarty, McCarty Farms, believes farmers can build a transparent information bridge to consumers with good record-keeping. “I think it’s the baseline that all farmers need to begin with,” says McCarty, whose operation is made up of five dairy farms – three in western Kansas, one in southwest Nebraska, and one in west-central Ohio – and a milking herd of approximately 13,000 cows.

Empirical data provide a foundation of facts that farmers can use to start sharing their specific stories. For farmers who haven’t gathered or used data before, McCarty says to start small to keep from being overwhelmed.

“It can be as simple as using your smartphone to take photos of implementing no-till practices on your farm,” McCarty says.

Good records also can help you take the second step in the process of transparency, which McCarty calls the verification process. “Without solid record-keeping it’s very difficult to undergo the various animal welfare audits or environmental sustainability audits,” he explains. “Things like being certified organic, animal-welfare certified or you name it, these are things increasingly important to consumers, and you need solid records to be able to verify that what you’re saying you’re practicing on your farm is real and true.”

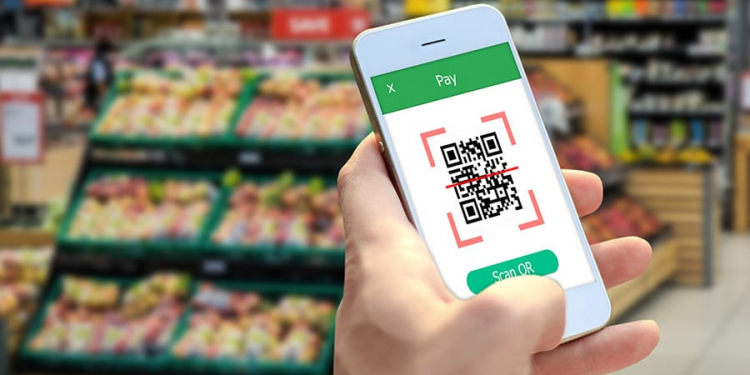

Rick Stein, vice president of fresh foods at FMI believes technology can also help in the consumer education process and references the SmartLabel initiative as one example. The initiative has grown into a database that tracks 170,000 nutrients, nearly 400,000 ingredients and 5 million claims.

“When consumers scan a QR code, it gives them all kinds of data in terms of not only nutritional information, but it can give them information in terms of where (the product) was grown and how it was grown and how it reached market shelves,” Stein says. As farmers work to connect with consumers, McCarty says to consider additional, less traditional ways to reach them.

“The initial idea is to go to the person sitting at their kitchen table, but there’s some middle ground there and it can be a bit more efficient – like what does Walmart want, what does Kroger want?” McCarty says. “At times I can get a clear picture of where I need to position my business and my practices by trying to understand their goals and objectives for their companies much easier than I can if I try to understand what the consumer wants, because the consumer is very broad-based,” he adds.